Touch of Evil was released by Universal in 1958 on the bottom half of a double bill, in a version butchered by the studio over Welles’s passionate protests.

By 1965 Touch of Evil still had virtually no recognition in the United States. Though it earned high praise from Truffaut and Godard in 1958, Americans generally thought it a sleazy crime picture. By late 60s, the film was regarded as international film masterpiece.

The “new” version makes it even clearer that Touch of Evil is a flat-out all- cylinders-running, eye-popping masterpiece, one of a few monumental 1950s swan songs marking the end of the great epoch of traditional studio filmmaking. It belongs alongside Vertigo and The Searchers as a tribute to the kind of directorial vision that used the machinery of the studio to create a work of pure visual poetry, translating a script into stunningly original compositions and camera movements that unify the narrative and the imagery. Viewers with art-house standards of classy dialogue and acting who gravitate to the obvious stylistic flourishes of Citizen Kane might still prefer that film to the integrated visual field of Touch of Evil. But if you're open to the idea that the visual qualities of depth and perspective are a key part of the language that film speaks, Touch of Evil should offer nearly two hours of ecstatic if uneasy pleasure: together the style and script intertwine the themes of moral corruption and mental breakdown.

Welles, creates a labyrinthine film, wedding a common motif in Welles films-that of an oversize character on a quest - to another key Welles theme: self- deception. Except for Vargas and Susan, the characters want to be something they’re not. Bitterness fostered by the unsolved murder of his wife three decades earlier makes Quinlan want to be a cop who always gets his mantas his manufacturing of evidence. It may be that, as he says, he framed "nobody that wasn’t guilty," but clearly Welles condemns Quinlan's violations of the law.

The convergence of the two narratives further underlines Quinlan's centrality. And long takes of characters engaged in parallel if unrelated actions reinforce the way that characters echo one another. Indeed, the film seems a giant web, a fatalistic machine driven by duplicity that brings characters together even when they have no wish to be connected.

One of the new version's chief glories is its revision of the justly famous opening shot. Not only were titles originally printed over it, obscuring much of the action and detracting from the shot's complexity, but Henry Mancim's music crowded out much of the ambient sound Welles had so carefully scored. Mancini's music has been removed from the opening, and now we see and hear this shot in all its power—the planting of the bomb by a shadowy figure, Rudy Linnekar and his girlfriend driving across the border, and Vargas crossing at the same time, seeking "a chocolate soda for my wife." Welles's virtuosic camera (aided by the brilliant cinematographer Russell Metty, whose complex composition and lighting work as well for Welles as they did for Douglas Sirk) moves sideways, cranes up, cranes down, moves in and out, and shifts direction, establishing a maze of movements and interconnections: more than once Vargas and Susan's movement parallels that of Linnekar's car, linking their destiny to his imminent death. The sound design—music emerging from various establishments, growing louder and quieter—reveals the importance of Welles's previous work in radio: he's particularly sensitive to the way sound can evoke space. Here the shifting aural perspectives combine with the shifting camera movements to plunge us into an unstable, nearly chaotic world full of momentary convergences.

Virtually every composition, cut, and camera movement in Touch of Evil can be justified as a visual correlative to the narrative.

But as masterful as Welles's filming is, what makes Touch of Evil a staggering masterpiece is the global quality of his style, which causes every image to echo almost every other in the film. Using a wide-angle lens (16mm) both affords deep focus—foreground and background alike are sharp-and seems to stretch or curve the space. Welles's intensely physical approach makes one feel the images to be collages of sensuous surfaces. Together his roving camera, complex lighting, and shifting perspectives seem parts of the filmmaker's quest to forge an intimate contact with every object in the world.

Quinlan is grotesquely fat (already round, Welles had himself padded for the role) because he substitutes candy bars for his previous addiction: "It's either the candy or the hooch," he says. Excessive ingestion of food or liquor can blur the distinctions between oneself and the world; often the addict seeks to recover a kind of primal unity lost since the undifferentiated state of earliest childhood. Welles also gives Quinlan a lost love—his murdered wife—as a metaphor for the impossibility of his quest: lacking her, he seeks to dissolve himself. But as any alcoholic or overeater knows, such attempts at recovering unity are bound to fail.

The film’s most pivotal moment, combining its dual themes of the wish for unity and its inevitable breakdown, is a cut very near the end. Menzies calls to Quinlan from outside Tanya's, trying to lure him out and secure his confession on a concealed tape recorder. As Quinlan emerges, we see him from the extreme low angle Welles has already used for him several times— most notably the first time we see him, emerging from a car like a suddenly congealing giant blob. Such images, further exaggerating his belly, make Quinlan seem both powerful and grotesque. Suddenly we cut to a reverse angle shot from behind Quinlan, with the camera rising above him as he leaves Tanya's and plunges into the night and his own doom. This shift seems to twist and turn and reshape space, as the curves created by the wide-angle lenses used in both shots merge at the point of the cut. This is the last of the film's unifying moments.

In the extraordinary final scene, the camera gives up its striving to unify space. Instead we proceed past disjunct shapes-bridges, canals, oil derricks, drainage ditches, garbage—all of which seem metaphors for the breakdown of Quinlan’s mind. An absurdly phallic oil derrick seen from below, for example, is the perfect sign of his failed ambitions as he's faced with the imminent unraveling of his identity as an honest cop. A passionate quest for a lost unity with the sensual world—accompanied almost from the beginning with an acknowledgment of that quest's impossibility, mirroring the larger themes of love and its loss, life and death—is the outsize true subject of a low- budget crime film, ironically labeled by a contemporary Variety review "not a 'big’ picture.’’

5+ / 5

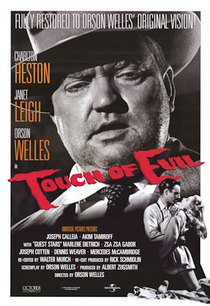

Director: Orson Welles

Staring: Orson Welles, Charlton Heston, Janet Leigh

LEARN MORE BELOW

RSS Feed

RSS Feed