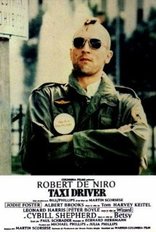

Taxi Driver has a lot of negative aspects, but it would be silly to shrug off its baroque visuals and its high-class actor, Robert De Niro, whose acting range is always underscored by a personal dignity. He's very good at wild manic scenes and better at poignant introversion: a man watching TV in a trance and eating while not looking at his food, or giving the sense of tense repression. Every scene combines the frantic and the still, almost simultaneously. The film has a good sense of modern paralysis, people flailing about energetically but not moving an inch (“twelve hours of driving a taxi and I still can’t sleep").

De Niro’s Travis Bickle, wanting to be ”a person like other people" to be a pair with the wondrous purity of his political campaigner blonde (Cybill Shepherd) joins Alice Hyatt and Mean Streets’s always-repenting Charlie in Martin Scorsese's angst oeuvre. His movies are about youth's dreams squelched by the adult verities, the charismatic fullness of a jungle-cat punk (Keitel, trapped in Sport's coded character), a feisty twelve-year-old whore (Jodie Foster, who has the shiny complexion, hair, and bright eyes of neither lower East Side nor a baby prostitute), a vulgar and good-natured cabbie (Peter Boyle, who like a Thirties character actor, tells Manhattan versions of tall tales to his buddies at the Belmore Cafeteria)."

The apprehension about an eagermessy world is transmitted through a sancing technique in which Scorsese's unique effect is the number of optical moves that are made in a tight space, seldom using a character’s point of view for his camera position. He has a romantic appreciation for Life which remembers an actor's best moves and generously supplies the time for "full-scale exposition.

New York street noise is replaced by a writhing, intense Bernard Herrmann music track, Saxophones and a pulled-taffy Muzak sound that almost - buries the visuals. The hero's taxi is mostly seen in abstract effects pulling up or taking off, the windows awash with ingeniously engineered colored lights; in one quick spray of inserts, there is a rhythm series of the same stop light,

Basing its tortured hackle hero vaguely on the pasty-faced Arthur Bremer, who, frustrated in his six attempts to kill Nixon, settled on maiming George Wallace for life, “Taxi Driver” not only waters down the unforgettable (to anyone who's read his diary) Bremer, but goes for traditional plot sentimentality. Bremer, as he comes across in his diaries, was mad every second, in every sentence, whereas the Bickle character goes in and out of normality as the Star System orders. The Number One theme in the Arthur Brerner diary is “I Want to Be A Star.” Having dropped this obsession as motivation, the film falls into a lot of motivational problems, displacing the limelight urge into more Freudian areas (like sexual frustration) and into religious theories (like ritual self-purification). The star or celebrity obsession is a Seventies fact—the main thing that drives people these days - compared to the dated springboards in Paul Schrader's script. Instead of Bremer's media dream, getting his name into the New York Times headlines, this script is set on pulp conventions: a guy turns killer because the girl of his dreams rejects him. The girl of his dreams, a squeaky-clean WASP princess, is yet another cliche assumption: that the outsiders of the world are yearning to connect to the symbols of well-washed middle-class gentility.

Busily trying to turn pulp into myth the film runs into all kinds of plot impossibles:

(1) A shy guy converts himself into a brutal killer after scenes in which he is a smart-ass with an FBI agent, a near matinee idol with his Miss Finishing School, and an unsophisticated, normal Lindbergh type with a teen prostitute. The latter girl similarly goes from street-hardened and cynical to open and cheerful, well-nourished and unscarred, in one twelve-hour time interval.

{2} The cabbie, after having readied himself with push-ups, chin-ups, burning dead flowers, and many hours of target practice, guns down a black thief in a Spanish deli. The brutality, which is extended by the store-owner golfing the victim's corpse with a crowbar, is never touched by the police.

(3) A taxi driver who's slaughtered three people, been spotted twice by the FBI, and has enough unlicensed artillery strapped to his body to kill a platoon, is hailed as a liberating hero by the New York press.

(4) A Secret Service platoon, grouped around a rather minor campaign speech on Columbus Circle, fails to spot and apprehend a fantastic apparition: a madly grinning young man who is wearing an oversized jacket on a summer day sunglasses, and has his head shaved like a Mohawk brave, with a strip of carpeting for the remaining hair.

The movie relishes getting blacks off as malevolent debris that proliferates on the streets. Everywhere the cab moves there is a black marker representing the scumrniest low point of city life. A muscular black walks through a barely noticing crowd on a narrow sidewalk; he's muttering loudly "I'll kill her, I’ll kill that bitch." A gang of black teen-agers bursts out of an alley hurling garbage at Travis’s Checker. Three little black kids torment a black whore, who, seeming used to such defiling, lashes back with her shoulder bag.

The extent of his sexism and racism is hedged. While Travis stares at a night world of black pimps and whores, all the racial slurs come from fellow whites. In fact, Travis tries to pick up a mulatto candy seller in an interesting porno-theater scene. He tries to joke with this bored, rather pretty but definitely uninterested popcorn girl who's reading a fan mag, and she calls the manager.

A chief mechanism of the script is power: how people either fit or don't fit into the givens of their status, and the power they get from being socially snug. Travis’s dream girl has power because she has a certain golden beauty and doesn't question or rebel against her face or her position as political campaigner.Various pimps are shown as editorialized icons of illegal power. The cabbies, more or less at peace with themselves are glimpsed as a gang not fighting job or status. The film shows the facts of being in or out. Everyone plays this 'power game but Travis—he can't figure what kind of game he wants to play.

Travis seldom relaxed in any territory except his animal-lair room, works his way through a violent landscape which is curiously pluralist in its technique. One frame isn't promoted over another, there is no favored composition, there are constant changes of style, pace, and arrangement. The only constant is that the hero, in crowds or alone, in broad daylight or total darkness, appears to be alone in a dense funnel of cave of space.

4 / 5

Director: Martin Scorsese

Staring: Robert De Niro, Jodie Foster, Harvey Keitel, Cybill Shepherd, Peter Boyle

De Niro’s Travis Bickle, wanting to be ”a person like other people" to be a pair with the wondrous purity of his political campaigner blonde (Cybill Shepherd) joins Alice Hyatt and Mean Streets’s always-repenting Charlie in Martin Scorsese's angst oeuvre. His movies are about youth's dreams squelched by the adult verities, the charismatic fullness of a jungle-cat punk (Keitel, trapped in Sport's coded character), a feisty twelve-year-old whore (Jodie Foster, who has the shiny complexion, hair, and bright eyes of neither lower East Side nor a baby prostitute), a vulgar and good-natured cabbie (Peter Boyle, who like a Thirties character actor, tells Manhattan versions of tall tales to his buddies at the Belmore Cafeteria)."

The apprehension about an eagermessy world is transmitted through a sancing technique in which Scorsese's unique effect is the number of optical moves that are made in a tight space, seldom using a character’s point of view for his camera position. He has a romantic appreciation for Life which remembers an actor's best moves and generously supplies the time for "full-scale exposition.

New York street noise is replaced by a writhing, intense Bernard Herrmann music track, Saxophones and a pulled-taffy Muzak sound that almost - buries the visuals. The hero's taxi is mostly seen in abstract effects pulling up or taking off, the windows awash with ingeniously engineered colored lights; in one quick spray of inserts, there is a rhythm series of the same stop light,

Basing its tortured hackle hero vaguely on the pasty-faced Arthur Bremer, who, frustrated in his six attempts to kill Nixon, settled on maiming George Wallace for life, “Taxi Driver” not only waters down the unforgettable (to anyone who's read his diary) Bremer, but goes for traditional plot sentimentality. Bremer, as he comes across in his diaries, was mad every second, in every sentence, whereas the Bickle character goes in and out of normality as the Star System orders. The Number One theme in the Arthur Brerner diary is “I Want to Be A Star.” Having dropped this obsession as motivation, the film falls into a lot of motivational problems, displacing the limelight urge into more Freudian areas (like sexual frustration) and into religious theories (like ritual self-purification). The star or celebrity obsession is a Seventies fact—the main thing that drives people these days - compared to the dated springboards in Paul Schrader's script. Instead of Bremer's media dream, getting his name into the New York Times headlines, this script is set on pulp conventions: a guy turns killer because the girl of his dreams rejects him. The girl of his dreams, a squeaky-clean WASP princess, is yet another cliche assumption: that the outsiders of the world are yearning to connect to the symbols of well-washed middle-class gentility.

Busily trying to turn pulp into myth the film runs into all kinds of plot impossibles:

(1) A shy guy converts himself into a brutal killer after scenes in which he is a smart-ass with an FBI agent, a near matinee idol with his Miss Finishing School, and an unsophisticated, normal Lindbergh type with a teen prostitute. The latter girl similarly goes from street-hardened and cynical to open and cheerful, well-nourished and unscarred, in one twelve-hour time interval.

{2} The cabbie, after having readied himself with push-ups, chin-ups, burning dead flowers, and many hours of target practice, guns down a black thief in a Spanish deli. The brutality, which is extended by the store-owner golfing the victim's corpse with a crowbar, is never touched by the police.

(3) A taxi driver who's slaughtered three people, been spotted twice by the FBI, and has enough unlicensed artillery strapped to his body to kill a platoon, is hailed as a liberating hero by the New York press.

(4) A Secret Service platoon, grouped around a rather minor campaign speech on Columbus Circle, fails to spot and apprehend a fantastic apparition: a madly grinning young man who is wearing an oversized jacket on a summer day sunglasses, and has his head shaved like a Mohawk brave, with a strip of carpeting for the remaining hair.

The movie relishes getting blacks off as malevolent debris that proliferates on the streets. Everywhere the cab moves there is a black marker representing the scumrniest low point of city life. A muscular black walks through a barely noticing crowd on a narrow sidewalk; he's muttering loudly "I'll kill her, I’ll kill that bitch." A gang of black teen-agers bursts out of an alley hurling garbage at Travis’s Checker. Three little black kids torment a black whore, who, seeming used to such defiling, lashes back with her shoulder bag.

The extent of his sexism and racism is hedged. While Travis stares at a night world of black pimps and whores, all the racial slurs come from fellow whites. In fact, Travis tries to pick up a mulatto candy seller in an interesting porno-theater scene. He tries to joke with this bored, rather pretty but definitely uninterested popcorn girl who's reading a fan mag, and she calls the manager.

A chief mechanism of the script is power: how people either fit or don't fit into the givens of their status, and the power they get from being socially snug. Travis’s dream girl has power because she has a certain golden beauty and doesn't question or rebel against her face or her position as political campaigner.Various pimps are shown as editorialized icons of illegal power. The cabbies, more or less at peace with themselves are glimpsed as a gang not fighting job or status. The film shows the facts of being in or out. Everyone plays this 'power game but Travis—he can't figure what kind of game he wants to play.

Travis seldom relaxed in any territory except his animal-lair room, works his way through a violent landscape which is curiously pluralist in its technique. One frame isn't promoted over another, there is no favored composition, there are constant changes of style, pace, and arrangement. The only constant is that the hero, in crowds or alone, in broad daylight or total darkness, appears to be alone in a dense funnel of cave of space.

4 / 5

Director: Martin Scorsese

Staring: Robert De Niro, Jodie Foster, Harvey Keitel, Cybill Shepherd, Peter Boyle

RSS Feed

RSS Feed