| A long way to go to a “future worth fighting for.” Released in 2016, Overwatch (Blizzard Entertainment, 2016) is a team based first person shooter game set in a future Earth. Selling over 50 million copies (D’Anastasio 2022), The game revolves around two teams of six players picking from a cast of playable characters or “Heroes” hailing from diverse backgrounds to do battle across various locations set around the globe. |

Overwatch is a game that is often praised for its focus on inclusivity and diversity in its character design as quoted by the game director of Overwatch Jeff Kaplan “What we cared about was creating a game and a game universe and a world where everybody felt welcomed. And really what the goal was inclusivity and open mindedness” (Kaplan, 2017, 31:35).

Prior to it’s closing before the release of its sequel it had a pool of 32 playable heroes, of 14 were women, 2 were canonically confirmed to be LGBTQ+ and one who suffered from a disability (Overwatch, 2022). However, while officially having more female and LGBTQ characters create exposure and representation for women and other marginalized groups which can in turn act as tools for empowerment and change in the gaming community, the same tools when used improperly can also serve to feed further into stereotypes and discriminatory beliefs and practices. When making the narrative decision to label a character’s identity, Blizzard takes away the individual agency of each player to write their own story (Dym et al.,2018) and has now shouldered the responsibility of developing respectful and complex characters, staying truthful to the communities that they are supposed to represent. Through the weighted choices presented in its game systems and the gender biased culture of its social spaces Overwatch sends mixed messages which stand in the way of the inclusive spirit of the game. In spite of its progressive ideals, the design choices behind hero diversity in Overwatch causes shallow character representation, which perpetuates stereotyping and gender norms, deepening the divides in the gaming community.

Diversity as a checklist

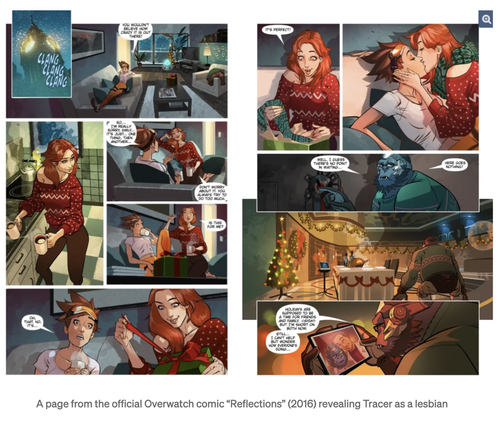

In games like Overwatch, playable characters are fully written by the developers and not player generated, this comes with its own set of unique benefits and drawbacks. While it sacrifices the player’s affordance to create an avatar which represents them, having pre written characters allow the developers more opportunities to not only create rich and engaging character narratives, but also more chances to integrate that narrative within the storyworld. This allows developers to take advantage of games as a storytelling medium and provide an immersive and interactive story experience to captivate players. However, with its potential boons comes its own set of potential pitfalls and this is perhaps where Blizzard may have missed the mark. With the reveal of Overwatch’s two non-heterosexual characters, Blizzard chose to digress the reveal in a few images and speech bubbles, shown through a series of digital online comics that were separate from the game with no prior hints existing within the game itself. When a character identity is defined it is a choice to tell the players who the character is, but when that identity isn’t adequately expressed and integrated within the gameworld, it causes a suspension of belief between the player and the narrative, when Soldier:76 was revealed to be gay, there was community pushback saying that his sexuality was retconned because the Soldier:76 that they got to know up to that point had no indication or sign of ever having any sexual feelings (Välisalo et al.,2022). While the representation of minorities is a step in the right direction, if the goal of Overwatch is to truly push for inclusivity within its player base then the game “needs the input of sexuality, gender and ethnicity as more than just tidbits in the game narrative in transmedia expansions more or less distant from the actual gameplay” (Välisalo et al.,2022). With no mention of the struggles of living through homophobia, and no representation of the difficulties of living in a heteronormative society impacting their development, a character being homosexual is nothing more than a label. This lack of expression creates a static and quantified approach to character design and is an example of telling instead of showing. Defining character identity through a checklist rather than their lived experiences is inauthentic and cheapens the experiences of the LGBTQ people that these characters are meant to be relatable to.

In games like Overwatch, playable characters are fully written by the developers and not player generated, this comes with its own set of unique benefits and drawbacks. While it sacrifices the player’s affordance to create an avatar which represents them, having pre written characters allow the developers more opportunities to not only create rich and engaging character narratives, but also more chances to integrate that narrative within the storyworld. This allows developers to take advantage of games as a storytelling medium and provide an immersive and interactive story experience to captivate players. However, with its potential boons comes its own set of potential pitfalls and this is perhaps where Blizzard may have missed the mark. With the reveal of Overwatch’s two non-heterosexual characters, Blizzard chose to digress the reveal in a few images and speech bubbles, shown through a series of digital online comics that were separate from the game with no prior hints existing within the game itself. When a character identity is defined it is a choice to tell the players who the character is, but when that identity isn’t adequately expressed and integrated within the gameworld, it causes a suspension of belief between the player and the narrative, when Soldier:76 was revealed to be gay, there was community pushback saying that his sexuality was retconned because the Soldier:76 that they got to know up to that point had no indication or sign of ever having any sexual feelings (Välisalo et al.,2022). While the representation of minorities is a step in the right direction, if the goal of Overwatch is to truly push for inclusivity within its player base then the game “needs the input of sexuality, gender and ethnicity as more than just tidbits in the game narrative in transmedia expansions more or less distant from the actual gameplay” (Välisalo et al.,2022). With no mention of the struggles of living through homophobia, and no representation of the difficulties of living in a heteronormative society impacting their development, a character being homosexual is nothing more than a label. This lack of expression creates a static and quantified approach to character design and is an example of telling instead of showing. Defining character identity through a checklist rather than their lived experiences is inauthentic and cheapens the experiences of the LGBTQ people that these characters are meant to be relatable to.

Part of fun in game comes from immersion and narrative and there is no better place to see this then in player made content, even in games that do not give means to publish such creations in game, content will find it’s space on external sites, such as videos on YouTube, or fan written narratives on websites such as Archive of Our Own (Dym et al.,2018). Where fans have fostered a sense of belonging to the game universe through written personal narratives connecting themselves or their own characters to those in the game. However, by canonically defining a character’s sexuality, a developer removes an aspect of ambiguity behind that character and denies the validity of any other claim that players might have in fan written narrative. “Video games will never satisfy fans’ desire for diversity with a magical number of token characters” (Dym et al.,2018). By making the decision to define the sexuality of a character through external media separated from the game Blizzard has not only taken away from player agency to write their own narrative but also created a commodified and stereotypical representation of marginalized minorities.

Gaming culture & Gender Norms

As games have evolved to become more complex, so have the learning curves and skill floors associated with them. A steep learning curve can prove to be daunting to new players and can prove to be a barrier to entry, dissuading prospective players from picking up a game. However, in multiplayer games like Overwatch, such barriers can also stem from things outside of programmed game mechanics. To understand this we must first understand the classification system of the Heroes in Overwatch which are categorized into three classes, (Overwatch, 2022) they are:

Tanks: a role focused on leading pushes and mitigating incoming attacks from the enemy team.

Damage: a role focused on dealing damage and eliminating opposing players.

Support: a role focused on healing allies and providing buffs and support to enhance the performance of the rest of the team.

Gaming culture & Gender Norms

As games have evolved to become more complex, so have the learning curves and skill floors associated with them. A steep learning curve can prove to be daunting to new players and can prove to be a barrier to entry, dissuading prospective players from picking up a game. However, in multiplayer games like Overwatch, such barriers can also stem from things outside of programmed game mechanics. To understand this we must first understand the classification system of the Heroes in Overwatch which are categorized into three classes, (Overwatch, 2022) they are:

Tanks: a role focused on leading pushes and mitigating incoming attacks from the enemy team.

Damage: a role focused on dealing damage and eliminating opposing players.

Support: a role focused on healing allies and providing buffs and support to enhance the performance of the rest of the team.

From a game design perspective, this method of organization allows for the creation of particular sets of heroes designed to encourage distinct playstyles and as a result attract multiple types of players. Players who gleam enjoyment out of mechanical mastery and eliminating other players may prefer damage heroes, who often rely more on aim and mechanical skill, while players who wish to engage with the enemy in close combat to deny opportunities to the enemy team may play tank heroes who generally have less potential to eliminate enemies but are given tools to mitigate the effectiveness enemy attacks. However from a cultural perspective, the effects of this method of categorization factors heavily into the perpetuation of gender stereotypes and discrimination both within Overwatch as well as the gaming community as a whole (Zhou et al.,2021). Like its cast of characters, Overwatch attracts a diverse playerbase from around the world. As of 2017, the number of female players of Overwatch is at 16%, which is more than double the 7.4% percentile of women who play games in the FPS genre (Yee, 2018), a factor of this higher percentage might be a result of the greater inclusivity, cartoon violence, and the strong focus on teamwork and cooperation that Overwatch provides (Filimowicz, 2023). However, a larger female minority also comes with its own reflective set of gender norms. Research has shown that such norms Include the female tendency to play heroes in the support class conforming with the patriarchal expectation to take on a more supportive and nurturing role (Zhou et al.,2021). The norm that women were more likely to be the target of gender based harassment and that poor performance was a result of their gender rather than a lack of skill (Zhou et al.,2021). This pattern of discrimination creates a negative feedback loop where women are pressured from exploring other roles and pressured into playing support characters because they are easier in order to avoid conflict with their teammates (Zhou et al.,2021).

These stereotypes extend beyond the community and are also represented within the game itself. Four of the seven support characters in the game are female compared to the three female tank characters out of a pool of eight (Overwatch, 2022). As “Algorithms mimic reality” (Trammel et al.,2022) it should come as no surprise that a multiplayer game played by millions of people has elements of the real world issues of societal gender norms as well as the political controversy associated with them. The virtual ideological space of Overwatch has become a reflection of the values of society and the preconceived gender biases embedded within it.

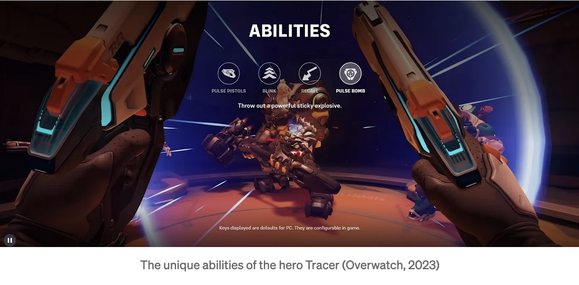

Promise of choice and punishing explorationPlayers tend to choose to play characters that represent them (Hodges et al.,2018), however that representation extends beyond character traits and identity to unique mechanics and affordances given to a hero. One of the appeals of hero based shooters is that each hero brings with them their own unique set of tools and abilities in which they can use within the game world. This provides players with a meaningful choice as to which character to play as it becomes a tradeoff, each character having their own unique advantages and drawbacks. Within other prominent character based competitive team games such as Valorant (Riot Games, 2020) or Apex Legends (Respawn Entertainment, 2019), these character choices are made at the beginning of the game and once decided are permanent for the rest of the match. If a player in one of these games encounters a situation that exacerbates the weaknesses of the character that they have chosen, they only have the defined affordances of that character to work with when finding a solution. This leads to one of the unique appeals of Overwatch; the ability to change your character at any point in the match. In Overwatch, whenever a hero gets eliminated or returns to their home room, they are allowed to swap characters giving players more choices to adapt to the situation at hand. (Overwatch, 2022) This provides a changing dynamic to provide players with greater opportunity for choice.

Promise of choice and punishing explorationPlayers tend to choose to play characters that represent them (Hodges et al.,2018), however that representation extends beyond character traits and identity to unique mechanics and affordances given to a hero. One of the appeals of hero based shooters is that each hero brings with them their own unique set of tools and abilities in which they can use within the game world. This provides players with a meaningful choice as to which character to play as it becomes a tradeoff, each character having their own unique advantages and drawbacks. Within other prominent character based competitive team games such as Valorant (Riot Games, 2020) or Apex Legends (Respawn Entertainment, 2019), these character choices are made at the beginning of the game and once decided are permanent for the rest of the match. If a player in one of these games encounters a situation that exacerbates the weaknesses of the character that they have chosen, they only have the defined affordances of that character to work with when finding a solution. This leads to one of the unique appeals of Overwatch; the ability to change your character at any point in the match. In Overwatch, whenever a hero gets eliminated or returns to their home room, they are allowed to swap characters giving players more choices to adapt to the situation at hand. (Overwatch, 2022) This provides a changing dynamic to provide players with greater opportunity for choice.

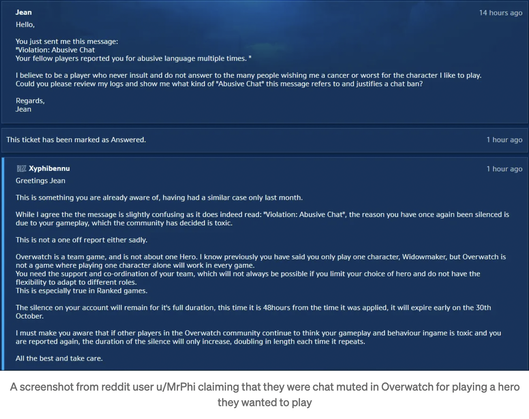

However, the mechanical differences between heroes mean that hero choice has a tangible effect on the quality of your team composition. Certain heroes tend to work better together than others.and the competitive nature of Overwatch mean that often, choosing a hero becomes more than just personal preference but also one of team cohesion and composition (Hodges et al.,2018). Potentially, this pressures players into picking heroes that are more aligned with what professional teams run rather than what they enjoy playing and can open up opportunities for players to berate or verbally assault their teammates for playing a hero they consider to not be optimal (Hodges et al.,2018). This punishment is made worse by the abuse of the report system, which automatically punishes player accounts if they are reported a certain number of times regardless of the validity of the reports themselves. As a result, the player’s hero choice becomes one not of which character they will have the most enjoyment playing but instead whether to play the character they enjoy knowing that they run the risk of facing verbal and textual harassment and potentially even suspension from the game. Additionally, should they decide to pick a hero they don’t enjoy for the sake of the team there is no actual incentive or reward given by the game. Overall, while the diverse cast of characters offer the initial impression of exploration and discovery for players, the game gives power to the competitive nature of the community and places undue pressure on players who enjoy playing heroes who are not dominant in the state of the game. When viewed from this angle, Overwatch is punishing players who are brave enough to go against the norms which goes against their goals of inclusivity.

Conclusion

Overwatch is a wildly successful and popular game and it’s goals toward inclusivity and acceptance toward all people is both noble and one that has clearly seen results. However, despite its acclaim Overwatch is not without its faults, and its popularity serves to increase the damage that those faults have on society. The poor integration of marginalized communities within the game’s heroes have created only superficial support for progressiveness while the prevalent gender biases within the game community cause and the punishment of players who would explore it’s boundaries have recreated the ideals of conforming to societal norms within Overwatch’s virtual world. While Overwatch champions diversity and inclusivity, it’s shortcomings show that it has a long way to go to reach a future worth fighting for.

References:

Blamey, C. (2022). Chapter 3: One Tricks, Hero Picks, and Player Politics: Highlighting the Casual-Competitive Divide in the Overwatch Forums. In M. Ruotsalainen, M. Törhönen, & V.-M. Karhulahti (Eds.), Modes of Esports Engagement in Overwatch (pp. 31–48). essay, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Dym, B., Brubaker, J., & Fiesler, C. (2018). “theyre all trans sharon”: Authoring Gender in Video Game Fan Fiction. Game Studies, 18(3). https://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/brubaker_dym_fiesler

D’Anastasio, C. (2022, April 29). Activision’s overwatch 2 is redefining the sequel. Bloomberg. Retrieved December 30, 2023, from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2022-04-29/activision-blizzard-s-overwatch-2-game-is-a-lot-like-the-original-review.

Filimowicz, M. Demographics by Age & Sex [Class handout]. WebCampus. https://canvas.sfu.ca/courses/79948/pages/demographics-by-age-and-sex?module_item_id=3038049

Hodges, D., & Buckley, O. (2018). Deconstructing who you play: Character choice in online gaming. Entertainment Computing, 27, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2018.06.002

[MrPhi]. (2016, October 28). 3rd chat ban for playing Widowmaker[Online forum post]. Reddit.https://www.reddit.com/r/funny/comments/9ihsdp/fantastic_view_from_google_earth/

Overwatch. Overwatch 2. (2016, May 24). https://overwatch.blizzard.com/en-us/

S, R. (2016). Cosplay at the 2016 New York Comic Con. flickr.com. Retrieved December 2, 2023, from https://www.flickr.com/photos/94565827@N05/30113751612/.

Trammell, A., & Cullen, A. L. (2022). A cultural approach to algorithmic bias in games. New Media & Society, 23(1), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819900508

Välisalo, T., & Maria Ruotsalainen, M. (2022). “Sexuality does not belong to the game” — Discourses in Overwatch Community and the Privilege of Belonging. Game Studies, 22(3). https://gamestudies.org/2203/articles/valisalo_ruotsalainen

Yee, N. (2018, June 14). Beyond 50/50: Breaking down the percentage of female gamers by genre. Quantic Foundry. https://quanticfoundry.com/2017/01/19/female-gamers-by-genre/

YouTube. (2017). D.I.C.E. Summit 2017 — IGN Live. YouTube. Retrieved November 30, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4SNdrEGSVUY&t=445s.

Zhou, R. J., Gao, Y., & Han, Q. (2021). Study of gender-based playing style stereotype in overwatch using machine learning analysis. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1883(1), 012028. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1883/1/012028

Games:

Overwatch [Video game]. (2016). Blizzard Entertainment.

Valorant [Video game]. (2020). Riot Games.

Apex Legends [Video game]. (2019). Respawn Entertainment.

Overwatch is a wildly successful and popular game and it’s goals toward inclusivity and acceptance toward all people is both noble and one that has clearly seen results. However, despite its acclaim Overwatch is not without its faults, and its popularity serves to increase the damage that those faults have on society. The poor integration of marginalized communities within the game’s heroes have created only superficial support for progressiveness while the prevalent gender biases within the game community cause and the punishment of players who would explore it’s boundaries have recreated the ideals of conforming to societal norms within Overwatch’s virtual world. While Overwatch champions diversity and inclusivity, it’s shortcomings show that it has a long way to go to reach a future worth fighting for.

References:

Blamey, C. (2022). Chapter 3: One Tricks, Hero Picks, and Player Politics: Highlighting the Casual-Competitive Divide in the Overwatch Forums. In M. Ruotsalainen, M. Törhönen, & V.-M. Karhulahti (Eds.), Modes of Esports Engagement in Overwatch (pp. 31–48). essay, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Dym, B., Brubaker, J., & Fiesler, C. (2018). “theyre all trans sharon”: Authoring Gender in Video Game Fan Fiction. Game Studies, 18(3). https://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/brubaker_dym_fiesler

D’Anastasio, C. (2022, April 29). Activision’s overwatch 2 is redefining the sequel. Bloomberg. Retrieved December 30, 2023, from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2022-04-29/activision-blizzard-s-overwatch-2-game-is-a-lot-like-the-original-review.

Filimowicz, M. Demographics by Age & Sex [Class handout]. WebCampus. https://canvas.sfu.ca/courses/79948/pages/demographics-by-age-and-sex?module_item_id=3038049

Hodges, D., & Buckley, O. (2018). Deconstructing who you play: Character choice in online gaming. Entertainment Computing, 27, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2018.06.002

[MrPhi]. (2016, October 28). 3rd chat ban for playing Widowmaker[Online forum post]. Reddit.https://www.reddit.com/r/funny/comments/9ihsdp/fantastic_view_from_google_earth/

Overwatch. Overwatch 2. (2016, May 24). https://overwatch.blizzard.com/en-us/

S, R. (2016). Cosplay at the 2016 New York Comic Con. flickr.com. Retrieved December 2, 2023, from https://www.flickr.com/photos/94565827@N05/30113751612/.

Trammell, A., & Cullen, A. L. (2022). A cultural approach to algorithmic bias in games. New Media & Society, 23(1), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819900508

Välisalo, T., & Maria Ruotsalainen, M. (2022). “Sexuality does not belong to the game” — Discourses in Overwatch Community and the Privilege of Belonging. Game Studies, 22(3). https://gamestudies.org/2203/articles/valisalo_ruotsalainen

Yee, N. (2018, June 14). Beyond 50/50: Breaking down the percentage of female gamers by genre. Quantic Foundry. https://quanticfoundry.com/2017/01/19/female-gamers-by-genre/

YouTube. (2017). D.I.C.E. Summit 2017 — IGN Live. YouTube. Retrieved November 30, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4SNdrEGSVUY&t=445s.

Zhou, R. J., Gao, Y., & Han, Q. (2021). Study of gender-based playing style stereotype in overwatch using machine learning analysis. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1883(1), 012028. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1883/1/012028

Games:

Overwatch [Video game]. (2016). Blizzard Entertainment.

Valorant [Video game]. (2020). Riot Games.

Apex Legends [Video game]. (2019). Respawn Entertainment.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed