Cinematography

Cinematographer Gregg Toland considered "Citizen Kane" the high point of his career. Everyone saw at once that the film didn't look like most American movies of its era. There is not an indifferently photographed image in the film. Even the exposition scenes - normally dispatched with efficient medium two-shots - are startlingly photographed. Deep-focus, low-key lighting, rich textures, audacious compositions, dynamic contrasts between foreground and background, backlighting, sets with ceilings, side lighting, steep angels, epic long shots juxtaposed with extreme close-ups, dizzying crane shots, special effects galore - none of these was new. But no one had previously used them in a such a "seven layer-cake profusion" (James Naremore).

Photographically, "Citizen Kane" ushered in a revolution, implicitly challenging the classical idle of transparent style that doesn't call attention to itself. The lighting in the film is generally in moderate high-key in those scenes depicting Kane's youth. As he grows older and more cynical, the lighting grows more darker, more harshly contrasting. Deep-focus photography involves the use of wide-angle lenses which tend to exaggerate the distances between people - an appropriate symbolic analogue for a story dealing with separation, alienation, and loneliness. The American cinema of the 1940s was to grow progressively darker, both thematically and photographically, thanks in big part to the enormous influence of "Citizen Kane."

Mise-en-scene

Coming from the world of live theater, Welles was an expert at staging action dynamically. Long shots are more effective medium for the art of mise-en-scene, and hence the film contains relatively few close shots. Most of the images are tightly framed and in closed form. Most of them are also composed in depth, with important information in the foreground, midground, and background. The proxemic ranges between the characters are choreographed balletically, to suggest their shifting power relationships. Almost all of the compositions are intricate and richly textured, at times baroquely ornate. But the visual complexity is not mere rhetorical ornamentation. The images are designed to reveal a maximum of information, often in an ironic manner. From the very beginning of his film career, Welles was a master of the mobile camera. In "Citizen Kane" camera movements are generally equated with the vitality and energy of youth. A static camera, on the other hand, tends to be associated with illness, old age, and death. In scenes depicting Kane as an old man, the camera is often far away, making him seem remote, inaccessible. Even when he is closer to the lens the deep-focus photography keeps the rest of the world at a distance, with vast empty spaces between him and other people. We are often forced to search the mise-en-scene to locate the characters. No one has used crane shots so spectacularly as Welles, but the virtuosity is not indulged for its own sake. The bravura crane shots embody important symbolic ideas.

Editing

The editing is calculated display of virtuosity, leaping over days, months, even years with casual nonchalance. He also uses several editing styles in the same sequence. Its difficult to isolate the editing because it often works in concert with the sound techniques. Often Welles used editing to condense a great deal of time, using sound as a continuity device.

Sound

Coming from the world of live radio drama, Welles was often credited with the inventing many film sound techniques. In radio, sounds have to evoke images. Welles applied this aural principle to his film soundtrack. With the help of his sound technician, James G. Stewart, Welles discovered that almost every visual technique has its sound equivalent. Each of the shots has an appropriate sound quality, involving volume, degree of definition, and texture.

Bernard Herrmann's musical score is similarly sophisticated. Musical motifs are assigned to several of the major characters and events. Many of these motifs are introduced in the newsreel sequence, then picked up later in the film, often in minor key, or played at a different tempo, depending on the mood of the scene.

Welles used sound for symbolic purposes and the film demonstrates that virtually every kind of visual has its aural counterpart.

Writing

"Citizen Kane" is often singled out for the excellence of its screenplay - its wit, its taut construction, its thematic complexity. The script authorship provoked considerable controversy, both at the time of the film's release and again in the 1970s.

Welles made extensive revisions on the first draft of the screenplay - so extensive that Mankiewicz denounced the film because it departed radically from his scenario. Nor did he want Welles's name to appear on the screenplay credit, and he took his case to the Writers Guild . At this time, a director was not allowed any writing credit unless he contributed 50% or more of the screenplay. In a compromise gesture, the guild allowed both of them credit, only with Mankiewicz receiving top billing.

When the controversy resurfaced in the 1970s with critic Pauline Kael contended that Welles merely added a few polishing touches to Herman Mankiewicz's finish product, the American scholar Robert L. Carringer settled the case once and for all. He examined the seven principal drafts of the screenplay, plus many last minute revision memoranda and additional sources. His conclusion was that Mankiewicz provided the raw material, Welles provided the genius.

5+ / 5

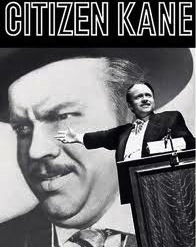

Director: Orson Welles

Staring: Orson Welles, Joseph Cotten, Dorothy Comingore, Agnes Moorehead, Everett Sloane

LEARN MORE BELOW

Cinematographer Gregg Toland considered "Citizen Kane" the high point of his career. Everyone saw at once that the film didn't look like most American movies of its era. There is not an indifferently photographed image in the film. Even the exposition scenes - normally dispatched with efficient medium two-shots - are startlingly photographed. Deep-focus, low-key lighting, rich textures, audacious compositions, dynamic contrasts between foreground and background, backlighting, sets with ceilings, side lighting, steep angels, epic long shots juxtaposed with extreme close-ups, dizzying crane shots, special effects galore - none of these was new. But no one had previously used them in a such a "seven layer-cake profusion" (James Naremore).

Photographically, "Citizen Kane" ushered in a revolution, implicitly challenging the classical idle of transparent style that doesn't call attention to itself. The lighting in the film is generally in moderate high-key in those scenes depicting Kane's youth. As he grows older and more cynical, the lighting grows more darker, more harshly contrasting. Deep-focus photography involves the use of wide-angle lenses which tend to exaggerate the distances between people - an appropriate symbolic analogue for a story dealing with separation, alienation, and loneliness. The American cinema of the 1940s was to grow progressively darker, both thematically and photographically, thanks in big part to the enormous influence of "Citizen Kane."

Mise-en-scene

Coming from the world of live theater, Welles was an expert at staging action dynamically. Long shots are more effective medium for the art of mise-en-scene, and hence the film contains relatively few close shots. Most of the images are tightly framed and in closed form. Most of them are also composed in depth, with important information in the foreground, midground, and background. The proxemic ranges between the characters are choreographed balletically, to suggest their shifting power relationships. Almost all of the compositions are intricate and richly textured, at times baroquely ornate. But the visual complexity is not mere rhetorical ornamentation. The images are designed to reveal a maximum of information, often in an ironic manner. From the very beginning of his film career, Welles was a master of the mobile camera. In "Citizen Kane" camera movements are generally equated with the vitality and energy of youth. A static camera, on the other hand, tends to be associated with illness, old age, and death. In scenes depicting Kane as an old man, the camera is often far away, making him seem remote, inaccessible. Even when he is closer to the lens the deep-focus photography keeps the rest of the world at a distance, with vast empty spaces between him and other people. We are often forced to search the mise-en-scene to locate the characters. No one has used crane shots so spectacularly as Welles, but the virtuosity is not indulged for its own sake. The bravura crane shots embody important symbolic ideas.

Editing

The editing is calculated display of virtuosity, leaping over days, months, even years with casual nonchalance. He also uses several editing styles in the same sequence. Its difficult to isolate the editing because it often works in concert with the sound techniques. Often Welles used editing to condense a great deal of time, using sound as a continuity device.

Sound

Coming from the world of live radio drama, Welles was often credited with the inventing many film sound techniques. In radio, sounds have to evoke images. Welles applied this aural principle to his film soundtrack. With the help of his sound technician, James G. Stewart, Welles discovered that almost every visual technique has its sound equivalent. Each of the shots has an appropriate sound quality, involving volume, degree of definition, and texture.

Bernard Herrmann's musical score is similarly sophisticated. Musical motifs are assigned to several of the major characters and events. Many of these motifs are introduced in the newsreel sequence, then picked up later in the film, often in minor key, or played at a different tempo, depending on the mood of the scene.

Welles used sound for symbolic purposes and the film demonstrates that virtually every kind of visual has its aural counterpart.

Writing

"Citizen Kane" is often singled out for the excellence of its screenplay - its wit, its taut construction, its thematic complexity. The script authorship provoked considerable controversy, both at the time of the film's release and again in the 1970s.

Welles made extensive revisions on the first draft of the screenplay - so extensive that Mankiewicz denounced the film because it departed radically from his scenario. Nor did he want Welles's name to appear on the screenplay credit, and he took his case to the Writers Guild . At this time, a director was not allowed any writing credit unless he contributed 50% or more of the screenplay. In a compromise gesture, the guild allowed both of them credit, only with Mankiewicz receiving top billing.

When the controversy resurfaced in the 1970s with critic Pauline Kael contended that Welles merely added a few polishing touches to Herman Mankiewicz's finish product, the American scholar Robert L. Carringer settled the case once and for all. He examined the seven principal drafts of the screenplay, plus many last minute revision memoranda and additional sources. His conclusion was that Mankiewicz provided the raw material, Welles provided the genius.

5+ / 5

Director: Orson Welles

Staring: Orson Welles, Joseph Cotten, Dorothy Comingore, Agnes Moorehead, Everett Sloane

LEARN MORE BELOW

RSS Feed

RSS Feed